About the Project

In 2003, The Village Bank completed a merger with another local bank, bringing new growth but also new challenges. By 2004, the commercial lending department was struggling to manage the substantial increase in business. They had no central way to track commercial loan applications, their status, and the documentation required to close them. The Senior Vice President of Lending asked me to help build a system to bring order to the chaos. Over the next two years, I developed Microsoft Access databases for both the commercial and residential lending departments, software that the bank used to close over 750 loans, representing more than $200 million in business. By 2006, my work had evolved beyond individual applications to proposing complete systems architecture for bank-wide communication and data integration.

The Problem Space

The lending team needed more than just a database. They needed a tool that fit seamlessly into their daily workflow. Commercial loans involve complex documentation requirements, multiple stakeholders, and constant status changes. Loans moved through multiple stages: from lead to application, processing, underwriting, closing, and post-closing. Over 50 document types needed tracking at various points in the process. Each role—Loan Officers, Portfolio Assistants, Management—needed a different view into the same data.

Without a central system, loan officers were wasting time hunting for information, applications were slipping through the cracks, and the team couldn't easily prioritize their pipeline. Any solution would need to handle this complexity while being intuitive enough that busy bankers would actually want to use it.

Domain Immersion

I was in my first internship at the bank, mostly basic IT work like reformatting computers, when the SVP of Lending approached me in April 2004. She showed me an Access database she was building for the department. After reviewing it, I told her it was a good start but probably needed to be redesigned from the ground up. She asked if I could do that. I said yes, but I was returning to school soon. I proposed a solution: I drew up a $5,000 contract to bring my brother up from Panama. He had just completed his Computer Science degree and could help build a prototype over the summer. She agreed.

That summer, while I took classes (including the Manufacturing Production course where I reverse-engineered PROSIM), I drove to the bank on Mondays to meet with staff and learn commercial lending from scratch. I had to understand loan stages, documentation requirements, and how different roles interacted with the same information. By the end of summer we had a working prototype. I continued refining it through my fall internship.

When I rolled out the initial software, I expected the team to embrace it immediately. After all, I had built it to their specifications. Instead, I got indifference. It wasn't that they hated it. They just weren't using it. The SVP asked me to sit down with Leah, one of the staff members who wasn't adopting it. I discovered she was copying data out of my database and putting it into Excel so she could color-code the fields. In my original design, each document being tracked was represented by a checkbox. But the feedback I got from Andy, the #2 loan officer, centered on what a pain it was to check and uncheck all those boxes.

This was a turning point. I spent several weeks watching how the lending team actually worked: what order they needed information, which tasks they repeated most often, how they discussed loans in their daily conversations. I was doing product design before I knew the term—user research, observing workflows, understanding that stated requirements and actual needs aren't the same thing. Then I completely redesigned the interface around their workflow rather than around database logic. For Leah, I built "The Leah Report," a custom view with color-coded document tracking built directly into the system. For Andy, I created "Andy's In Process," a streamlined pipeline view that eliminated the friction he'd complained about. Once the software matched how they thought about their work, both embraced it and never looked back.

I believed then, and still do, that technology needs to adapt to the needs of users, not the other way around. My boss in the IT department had a different philosophy. He believed users needed to be instructed on how to use technology. I saw their workarounds as specifications. The Manufacturing Production course I was taking that summer may have primed me to think about optimizing workflow, but this belief ran deeper. It shaped every project that followed.

Building the Solution

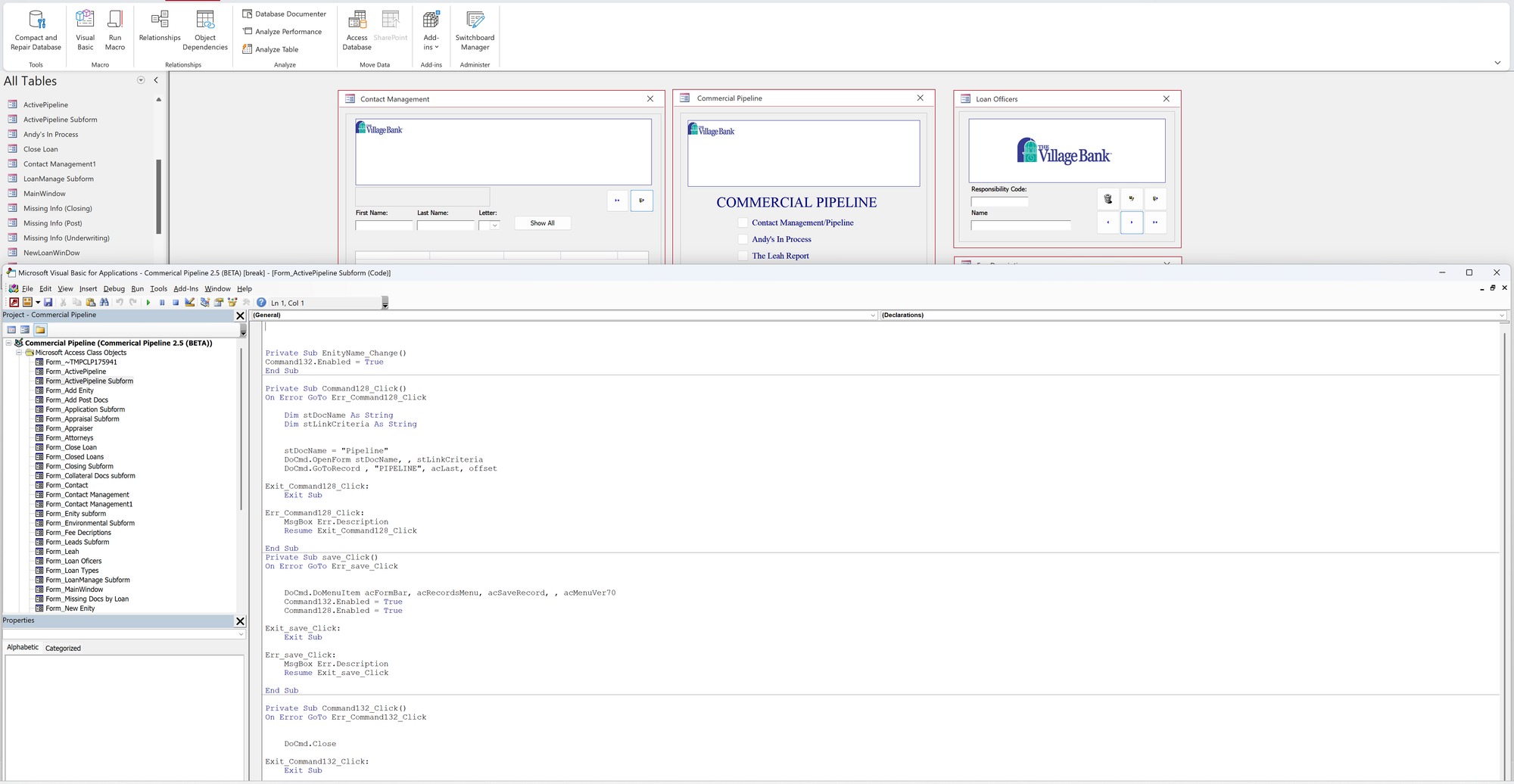

The system I built was substantial: 45 database tables to track entities, loans, and documents. 62 forms for data entry and navigation. 241 queries to retrieve and analyze information. Over 3,000 lines of VBA code to handle business logic and validation. This represented approximately 410-580 hours of development work, built incrementally from 2004 through 2006. I started in summer 2004, continued through my senior year of college (while juggling a full course load, two intramural sports, and volunteer tax prep), and expanded it after I joined the bank full-time in September 2005.

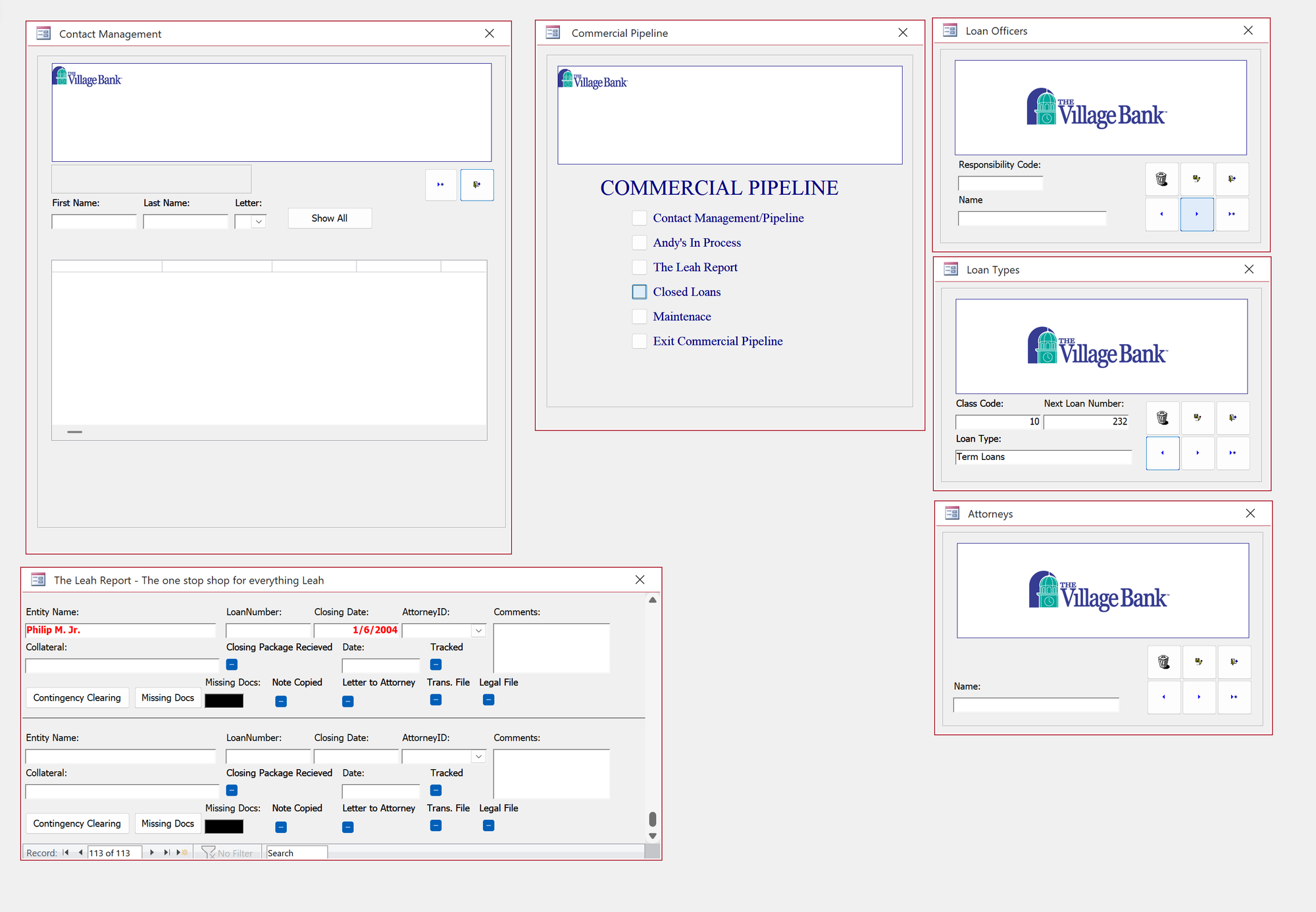

The reconstructed screenshots show the scope of the final system: the main Commercial Pipeline menu with its role-specific views, the VBA code powering the business logic, and forms like "The Leah Report" with its color-coded document tracking. The same feature Leah had been creating manually in Excel, now built into the software itself.

Systems Architecture and Infrastructure Planning (2006)

By early 2006, the success of multiple Access databases created a new challenge: how to make these tools available bank-wide. The bank was also struggling with systematic referral tracking and sales data sharing. I proposed a complete intranet implementation that would integrate all existing Access databases with web-based access, solving both the technical limitation and the communication breakdown.

The "Intranet Implementation Plan" I developed in March 2006 evaluated two architectural approaches: continuing with the existing proprietary Dovetail extranet or building an internal solution using WordPress (version 2.0.2, released just one month earlier). I performed formal SWOT analysis of both platforms, cited a US government study on open-source security, and designed a three-phase implementation plan with user feedback loops. WordPress was still relatively unknown in 2006, especially in conservative banking environments, but I recognized its potential for easier content management and active development community.

I also compared development frameworks: the Microsoft .NET stack (Windows Server, IIS, SQL Server, Visual Studio) versus the LAMP stack (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP). The proposal outlined the tradeoffs. .NET offered tighter integration with existing Access databases while LAMP provided cost savings through open-source software and greater flexibility. I calculated infrastructure costs, proposed security implementations including firewalls at all branches, and designed a three-phase rollout strategy.

While organizational priorities shifted and the proposed architecture wasn't implemented, the planning demonstrated capabilities beyond individual application development. By age 24, I was evaluating emerging technologies, performing business analysis, and designing complete system architectures, not just building databases.

Long-term Impact

My databases processed over $200 million worth of business for The Village Bank and became integral to how the lending departments operated. The system delivered concrete efficiency gains: a monthly report that previously took 3 hours to compile could now be generated in just 15 minutes, a 92% improvement. The pipeline automated loan number assignment, eliminating a manual process that had been error-prone, and tracked all documents needed to close each loan, reducing confusion about missing paperwork. Loan Originators, Credit Analysts, and Loan Services finally had a single place to look when they had questions about loan status.

The bigger lesson was about the gap between building something that works and building something people will actually use. The initial Commercial Pipeline taught me that successful software development isn't just about technical execution. It's about observation, iteration, and being willing to throw out your first approach when the people using it show you it doesn't fit their reality. Andy and Leah weren't being difficult. They were showing me what they actually needed.

This observation-driven approach shaped every project that followed, most directly in the work I did for S.B.C. Panama.